AI is no longer a future concept in primary care. It is already being used to support access, reduce admin, and improve how care is delivered.

The challenge many NHS leaders now face is not whether to engage with AI, but how to judge what is safe, useful and appropriate in a clinical setting. Many organisations are still starting with the wrong question, asking whether a tool is impressive or efficient, rather than whether it is predictable, bounded and governable in real clinical conditions. With frameworks for assessing risk and value still emerging, confidence often lags behind adoption. This is not because of reluctance, but because it is unclear which questions matter most, and which signals can be trusted.

Safe AI in primary care is not one thing

One of the biggest sources of confusion around AI is the assumption that it is a single, uniform capability. In reality, AI systems vary widely in how they behave, what they are designed to do, and how they should be used in healthcare.

At a basic level, AI systems are built to solve problems. Some are designed to tackle one very specific task, while others work across broader sets of inputs. Some systems will always return the same output when given the same input, much like a calculator. Others, particularly those working with language, may not.

That distinction matters in clinical settings. A tool that behaves predictably should be assessed very differently from one that reflects uncertainty in language or context. In primary care today, most AI tools are deliberately narrow in scope. They are built to support defined tasks such as transcription, summarisation, or patient navigation.

This focus is often misunderstood as limitation. In practice, it is what makes many tools safer, more reliable and easier to govern. Understanding what a system is designed to do, and just as importantly what it isn’t designed to do, is the first step towards building confidence around AI in primary care.

Why “accuracy” alone is the wrong question for safe AI in primary care

It is common to hear claims about AI being “90% accurate” or more. On its own, that figure rarely helps.

Accuracy can mean different things depending on the task. Focusing on a single accuracy figure can create false confidence, encouraging adoption before teams understand where failure is most likely to occur. Does it refer to how many words were captured? How well clinical terms were used? Whether key negatives were included? Or whether the final output was safe to rely on?

In clinical documentation, for example, missing information can be just as risky as incorrect information. An omission may not be obvious at first glance, but it can still affect decisions later on. This is why evaluation needs context. The more useful question is not “how accurate is this tool?” but “accurate at what, and measured how?”

It also explains why human review still plays an important role. AI can support clinicians, but it should not remove oversight where clinical judgement is required.

Safety, security and sovereignty are non-negotiable for safe AI in primary care

AI in healthcare must meet a higher bar than consumer technology. Not because it is less capable, but because the stakes are higher.

Safety is not just about avoiding obvious errors. It includes how systems behave over time, how risks are monitored, and how humans remain in-the-loop. A system that performs well on day one still needs to be safe on day three hundred.

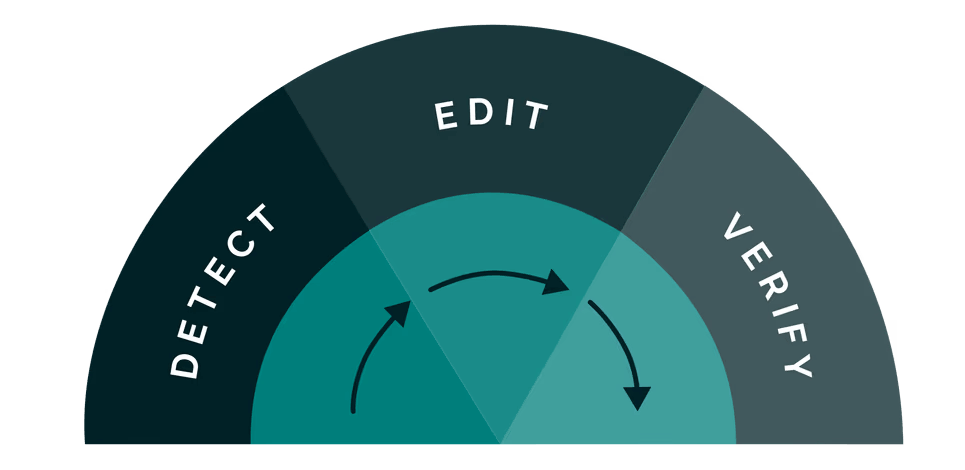

This challenge is particularly visible regarding safe use of AVT (ambient voice technology). Addressing this requires more than retrospective audits. It requires real-time safeguards that validate outputs against what was actually said, before documentation becomes part of the clinical record. For instance, TORTUS AI launched ‘The Shell’, a system that automatically removes 93% of detected hallucinations in clinical notes1. Emerging approaches like this that introduce secondary clinical safety layers reflect a growing recognition that AVT must be governed as a safety-critical system, not a convenience tool.

Under ‘The Shell’: steps taken to bring an added layer of safety to clinical notes

Security is about protecting patient data, not only from breaches, but from inappropriate use. This includes understanding where data is processed, who controls it, and what it is used for. Lastly, sovereignty matters because healthcare does not exist in a vacuum. UK primary care operates within specific regulatory, ethical, and clinical safety frameworks. AI tools need to align with that reality, not work around it.

Trust in AI is rarely built through bold claims. Instead, it develops through transparency, governance and clear boundaries around what technology will and will not do.

Adoption of safe AI in primary care is about people, not software

Even well-designed, safe AI in primary care can fail if it does not fit the realities of clinical work.

Adoption is often framed as training or change management, but in practice it comes down to whether a tool genuinely helps someone do their job better. That means understanding what clinicians actually do, what slows them down and what they worry about.

Common concerns about reliability, workload impact, personal clinical style and responsibility are not resistance. They are reasonable questions that need clear answers. When these are ignored or minimised, adoption stalls. Where safe AI in primary care is adopted successfully, it tends to start small. It addresses a clearly defined problem and involves people who understand local pressures and are trusted by their peers. It provides space to test, question and adapt, rather than demanding immediate compliance.

In primary care, where teams are already stretched, time and trust matter.

Related read: How AI can transform patient communication in primary care

Industry themes around safe AI in primary care

Across conversations with leaders and clinicians, consistent themes are emerging.

There is strong interest in AI, but only when it feels grounded in real clinical need. Leaders want clearer ways to assess both risk and value. Clinicians want tools that reduce load rather than shifting it elsewhere. There is little appetite for experimentation that creates uncertainty or additional work.

There is also a shared recognition that no single tool, session or metric provides all the answers. Confidence comes from understanding how different elements fit together, not from chasing the latest development.

What helps most is space for open discussion, practical framing and honest exploration of what “good” looks like in real settings.

Building confidence for safe AI in primary care

AI will continue to evolve, and its role in primary care will continue to grow. The question is no longer whether to engage, but how to do so safely and with confidence.

Being able to question, evaluate and adopt AI appropriately is becoming part of leadership in primary care. Those conversations work best when there is time to challenge assumptions, explore trade-offs and learn from others facing similar decisions

If you would like to have these conversations, join us on our UK Tour ‘Safe, secure and sovereign: Setting the standard for AI in primary care’. Free and CPD-accredited, hear from experts like Dr Dom Pimenta, founder and CEO of TORTUS AI, take part in open discussion and leave better equipped to make informed decisions about safe AI in primary care.